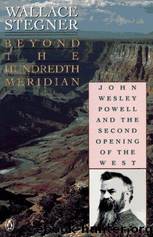

Beyond the hundredth meridian: John Wesley Powell and the second opening of the West by Wallace Earle Stegner

Author:Wallace Earle Stegner

Language: eng

Format: mobi, epub

Tags: West (U.S.) - History, Science & Technology, Adventurers & Explorers, General, United States, Scientists - United States - Biography, John Wesley, Scientists, Biography & Autobiography, Expeditions & Discoveries, West (U.S.), Powell, 19th Century, History

ISBN: 9780140159943

Publisher: Penguin

Published: 1992-03-01T03:55:49.145096+00:00

The justifications for reform were extensive, for every condition of land and climate, and every successive land law except the Timber Culture Act of 1873 worked against the city mechanic, immigrant, ambitious farm boy, or struggling three-time-pioneer who according to the myth would create the happy American yeomanry in the Western garden land. By the time the Homestead Act was passed in 1862, settlement was already at the edge of the subhumid belt. By the time the Timber Culture Act of 1873, the Desert Land Act of 1877, and the Timber and Stone Act of 1878 were piled upon the existing jumble of Pre-emption Act, public sales, railroad grants, Indian and soldiers’ scrip, and Homestead Act, there seemed to be many avenues to opportunity for the yeoman, and yet every one tempted him into an enterprise with a sixty-six per cent chance of failure. Despite incandescent enthusiasm for the Homestead Act at home and abroad, the forty years before 1900 saw no more than 400,000 families — about 2,000,000 people — homestead and retain government lands. Yet in that time the population of the United States grew by 45,000,000.12 The function of the open West as safety valve was greatly exaggerated if in that period 43,000,000 potential home-seekers either could not take advantage of free land or failed to hold their claims.

Suppose a pioneer tried. Suppose he did (most couldn’t) get together enough money to bring his family out to Dakota or Nebraska or Kansas or Colorado. Suppose he did (most couldn’t) get a loan big enough to let him build the dwelling demanded by law, buy a team and a sodbuster plow and possibly a disk harrow and a seeder and perhaps a binder — whatever elements of the multiplying array of farm machinery he had to have. Suppose he managed to buy seed, and lay in supplies or establish credit for supplies during the first unproductive year. Suppose he and his family endured the sun and glare on their treeless prairie, and were not demolished by the cyclones that swept across the plains like great scythes. Suppose they found fuel in a fuelless country, possibly digging for it, as Gilpin suggested, but more likely burning cow chips, and lasted into fall, and banked their shack to the window sills with dirt against the winter’s cold, and sat out the blizzards and the loneliness of their tundra-like home. Suppose they resisted cabin fever, and their family affection withstood the hard fare and the isolation, and suppose they emerged into spring again. It would be like emerging from a cave. Spring would enchant them with crocus and primrose and prairies green as meadows. It might also break their hearts and spirits if it browned into summer drouth. The possibilities of trouble, which increased in geometrical ratio beyond the 100th meridian, had a tendency to materialize in clusters. The brassy sky of drouth might open to let across the fields winds like the breath of a blowtorch, or clouds of grasshoppers, or crawling armies of chinch bugs.

Download

Beyond the hundredth meridian: John Wesley Powell and the second opening of the West by Wallace Earle Stegner.epub

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(26582)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(23062)

Out of India by Michael Foss(16837)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13292)

Small Great Things by Jodi Picoult(7102)

The Six Wives Of Henry VIII (WOMEN IN HISTORY) by Fraser Antonia(5488)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5070)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4937)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4791)

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4787)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4448)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4337)

Papillon (English) by Henri Charrière(4238)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4172)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4080)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(4010)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3940)

Aleister Crowley: The Biography by Tobias Churton(3622)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(3450)